“If there is an occupation suitable for women, it is photography.” So declared the Mexico City newspaper El Mundo in 1899. It went on: “They have the aptitude and an extraordinary manual dexterity and, above all, they serve better than a man to make portraits of women, arranging their headdresses and getting them in positions with a confidence and a thoroughness that would be impossible for persons of the opposite sex.”

The passage is quoted in the catalog for the exhibition Revolution & Ritual: The Photographs of Sara Castrejón, Graciela Iturbide, and Tatiana Parcero, on view at the Ruth Chandler Williamson Gallery at Scripps College through January 7, 2018. And while there is nothing in the exhibition to contradict the newspaper’s essential claim—these three women certainly do have an aptitude for photography—it may leave you smiling at the writer’s naiveté.

Sara Castrejón. Sin título (Coronel Amparo Salgado, Teloloapan, Abril 1911), 1911. Gelatin silver photographic postcard. 5 3/8 x 3 3/8 inches ©Consuelo Castrejón Family, Acapulco, Mexico.

Take Sara Castrejón’s remarkable portrait of Amparo Salgado, from 1911, depicting a young woman in a print dress posed against a painted studio backdrop. Has her headdress been capably arranged? Well, yes. Has she been got into position with confidence? Undoubtedly. But those may not be the first things you notice, given the rifle in her hand, the cartridge belts slung around her shoulder and waist, the insolent cock of her hip, and her expression of fierce and unapologetic resolve. This woman was a warrior—a colonel, in fact, in the army of Jesús Salgado, an agrarian revolutionary aligned with Emiliano Zapata in the Mexican Revolution. She was once described by another, clearly more traditional lady in the upper-middle-class set from which she hailed in Guerrero as “a crazy woman who ran around with the men, armed, and dressed in pants.” It may be, then, that the dress was merely a concession. Her defiant demeanor would imply as much.

Graciela Iturbide’s Nuestra Señora de Las Iguanas, Juchitán, Oaxaca, 1979 (Our Lady of the Iguanas, Juchitán, Oaxaca), 1979 Gelatin silver print. 16 x 20 inches ©Graciela Iturbide Courtesy of The Michael G. and C. Jane Wilson 2007 Trust.

Or take Graciela Iturbide’s equally stunning Nuestra Señora de Las Iguanas, Juchitán, Oaxaca (Our Lady of the Iguanas, Juchitán, Oaxaca), from 1979. Here we see another woman in a print dress framed in the traditional manner of a portrait, only in this case the “headdress” is a mess of iguanas. At the time the picture was taken, the subject, Sobeida Díaz, was on her way to market to sell these iguanas, which were alive, and carrying them on her head was simply the easiest way. (A contact sheet included in the catalog makes it clear that she found the photographer’s attentions to her circumstance amusing.) In the photograph, however, she has a mythic stature, appearing as a sort of Oaxacan Medusa, dauntless and prophetic, the reptiles twisting around her head as if enchanted as she gazes majestically into the distance.

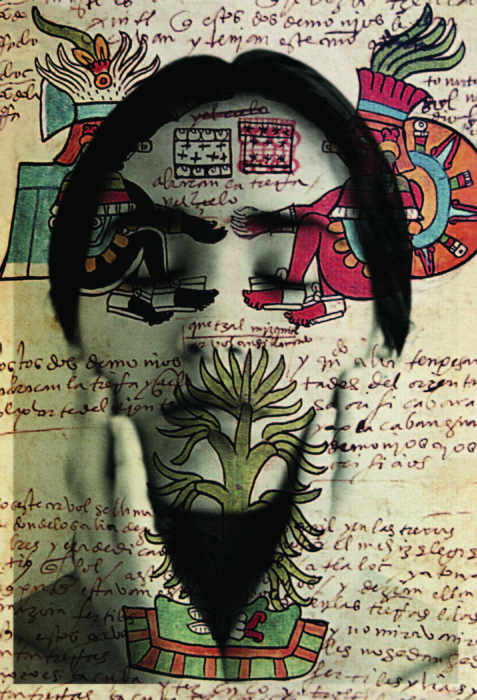

Tatiana Parcero’s Cartografía Interior #35 (Interior Cartography #35), 1996. Acetate and C-print. 24 1/4 x 17 1/2 inches.© Tatiana Parcero. Courtesy of Davis Museum, Wellesley College.

Or take Tatiana Parcero’s Cartografía Interior #35 (Interior Cartography #35), from 1996: a traditionally scaled head-and-shoulders portrait of a woman—the artist, as it happens—sans headdress, though framed by a dark halo of hair. First of all, her eyes are closed, denying the viewer access to that which a portrait is meant to reveal: the soul. What’s more, her face is obscured by other images, namely pre-Columbian figures and diagrams drawn from ancient Amerindian codices and columns of indecipherable script. The face is ghostly, printed on transparent acetate that layers over the other images, and appears as if subsumed by traces of an incomprehensible past. The feet of two elaborately decorated figures obscure the artist’s two closed eyes, while a tree grows over her mouth and nose.

Clearly, there is more going on in these photographs than confident positioning and headdress arrangement. Castrejón was one of the world’s earliest female war photographers. Iturbide has traveled the country extensively for decades to make her work, penetrating various layers of national and cultural identity in search of a deeper poetic essence. And Parcero transposes centuries of a violent and often oppressive history across the canvas of her own flesh. In assembling the work of these three very different female photographers from three different generations in Mexico, Revolution & Ritual presents a complex portrait, both of photography by women in Mexico and of Mexico through the lens of its female photographers.

The exhibition is part of a regional initiative by the Getty Foundation called Pacific Standard Time: LA/ LA, which provided more than $16 million in grants to more than 70 cultural institutions across Southern California to support exhibitions and projects exploring Latin American and Latinx art. LA/LA follows the Getty’s 2011 Pacific Standard Time: Art in L.A. 1945–1980, which took a similar approach to documenting the birth of the Los Angeles art scene. (For that phase of the initiative, the Williamson Gallery presented the fascinating and well-received Clay’s Tectonic Shift: John Mason, Ken Price, and Peter Voulkos, 1956-1968, which explored the radical turn in studio ceramics that occurred in Southern California during that period.) The Williamson Gallery received a $100,000 grant from the Getty to research and prepare Revolution & Ritual. The show is accompanied by a handsome 176-page catalog, with essays by Marta Dahó, Esther Gabara, and John Mraz.

“I looked for photographs by women whose art would span historical document and poetic expression,” says exhibition curator and Williamson Gallery director Mary MacNaughton ’70. She began with Graciela Iturbide, one of Mexico’s most prominent photographers, whose work was already represented in the Scripps collection. “I was interested in her iconic images of everyday life in indigenous communities and her fusion of documentary and cinematic vision. I thought she could be the fulcrum of an exhibition that examined a range of artistic visions reflecting different views of Mexican identity, from the national to the personal in subject matter, and historical to poetic in approach.”

Iturbide, born in Mexico City in 1942, came to photography in her late 20s by way of film school at the Centro Universitario de Estudios Cinematográficos. There she met Manuel Álvarez Bravo, one of the foremost photographers of the 20th century generally and certainly the most celebrated in Mexico. Álvarez Bravo, who was born in 1902 and lived to the age of 100, producing an exceptionally rich and diverse body of work, had played a defining role in the cultural renaissance that followed the revolution in Mexico, when a drive toward modernization—and, among artists, an embrace of modernism—was paired with renewed interest in the country’s precolonial roots.

Álvarez Bravo became a mentor and friend to Iturbide, and she traveled with him across Mexico as his assistant in the early 1970s, an experience that brought her in contact with the rural, indigenous village life that would come to inform so much of her later work and help to shape her understanding of the cultural depth and complexity of her country. Nuestra Señora de Las Iguanas, one of her best-known images and now an icon in the town of Juchitán, is one of many examples of works that emerged from Iturbide’s intimate associations with the markets, the festivals, the ceremonies, the protests—that is, with the people— of rural Mexico. Her allegiance to the integrity of these places can be seen in the fact that the location of each photograph is cited in its title, even when the photograph itself bears no obvious reference to physical geography.

Iturbide’s photographs, much like those of her mentor, are pictorially bold, often stark, and marvelously strange, charting an unusual path between the documentary and the mythological. Her works manage often to seem both obvious and mysterious, quotidian and magical, gritty and ethereal. In one, Carnaval, Tlaxcala (1974), an androgynous figure in a print dress, an enormous hat with pluming feathers, and an eerily frozen, doll-like mask stands alone on a flat, dusty plane skirted along the distant horizon with industrial buildings. In another, Mujer Ángel, Desierto de Sonora, Mexico (Angel woman, Sonora Desert, 1979), a draped woman in what could easily be taken for medieval dress sets out across a pristine desert landscape carrying a portable stereo. Iturbide’s later work is less sociological, more introspective, but if anything even more reverberant, with that mythological intensity somehow instilled in the simplest of objects or occurrences: the head of a snake slithering across a chipped linoleum floor; a flock of birds swarming a telephone pole; a shadow cast across a bullet-pocked wall.

The work of Sara Castrejón is a far cry from Iturbide’s in many ways. Born in 1888, Castrejón was a portrait photographer from a middle-class family in a remote town, Teloloapan, in the state of Guerrero. She photographed her subjects against baroque backdrops painted by her sister, with ornate pillars, balustrades, and urns filled with flowers. Yet she too studied in Mexico City, making the difficult journey from Teloloapan at the age of 18, and she was also clearly driven by a desire to give voice, through her work, to the people of her time. The fact that her time was one of revolution—the conflict began only a few years after she completed her training—seems only to have made that drive more urgent.

MacNaughton discovered Castrejón’s work in John Mraz’s book Photographing the Mexican Revolution: Commitments, Testimonies, Icons, from 2012. “I was struck by how she was little known,” MacNaughton says, “though she was the woman who most thoroughly photographed the Mexican Revolution.” Mraz worked with Samuel Villela, author of the only catalog devoted to her work (available only in Spanish), to produce the carefully researched and very informative essay that is his contribution to the Williamson’s exhibition catalog. Revolution & Ritual is the first U.S. exhibition to feature Castrejón’s work.

In addition to making the portraits, which are traditional in manner but for that aspect of historical context that would fill them with so many rifles and cartridge belts, Castrejón photographed the movement of troops and the camps around her town. The first picture she took of the revolution, which Mraz notes in his essay was also the first taken of the conflict’s southern insurrection, portrays a single-file column of Maderista-Salgadista troops on horseback entering the town of Teloloapan on April 26, 1911. Taken from a nearby rooftop, the photograph frames the column in such a way as to eclipse both its beginning and its end, giving the impression that it might stretch on for miles. From the start, then, Castrejón displays a keen awareness of the dramatic scale of the events unfolding around her as well as an attention to the role of the common man and woman within them.

Throughout Castrejón’s work, one is struck by her effort to document the plight—or perhaps to situate the meaning—of the individual against the impersonal scope of military action. Nowhere is this more evident than in a handful of portraits of men on the brink of their own executions. I say men, though most of them look more like boys, slight in stature and more desolate than villainous, as if bewildered by the forces they’ve found themselves caught up in. No reason is given for the executions, though the prisoners’ names are carefully noted in script on the surface of the images. These men confront the camera knowing, clearly, that this photograph will be the last to document their living selves, and Castrejón, also knowing this, does them the honor of recognizing them as individuals, unique in the world and beset, at this moment, with complex emotions.

The third photographer in the exhibition, Tatiana Parcero, might be said to invert the methods of the other two, accessing the history and the culture of her home country through the means of self- portraiture. Born in 1967, Parcero first studied photography in the 1980s with Pedro Meyer, a renowned documentary photographer who is known for his early adoption of digital techniques. She was strongly influenced by the artist-driven art scene of Mexico City in the 1990s, where performance and video were paramount. From the beginning, she has employed her body as a central element in the work, staging private performances for the camera, so to speak, that are captured and presented in fragments in the final prints.

Her technique of layering pairs of images—one printed on acetate that is mounted on Plexiglas and another behind that is printed on paper—dates to a series called Cartografía Interior from the late 1990s, made just after Parcero completed a graduate degree at New York University. The topmost image, which hovers, translucent, over the other, is almost always some fragment of Parcero’s own body (hands, face, back, feet); the background images are drawn from maps, codices, medical texts, and other historical pictorial sources. In Cartografía Interior, the background images come from pre-Columbian codices that lay out the history and geography of Mexico in very different terms from those adopted post-conquest, as well as from pre-modern anatomical illustrations. In this and in subsequent series, Parcero asks us to consider the fundamental proposition of mapping: the compulsion to document, contain, comprehend, and ultimately subjugate through imagery some hitherto unknowable territory, whether it be the geographical landscape of a continent or the biological interior of the body.

MacNaughton first encountered Parcero’s work, she says, at the Museum of Latin American Art in Long Beach. “Her distinctive compositions, which splice body fragments with historical documents, including Aztec codices and Spanish maps, are haunting images of layered identity, blending historical past and present experience,” she says. An elegant work called Universus #1, from 2013, in which a mandala-like diagram from 19th-century German biologist Ernst Haeckel hovers over Parcero’s slightly downturned forehead, is now contained in the Williamson Gallery’s permanent collection. Revolution & Ritual is not a survey and doesn’t claim to be. In presenting the work of three highly accomplished artists in depth, however, it allows for the consideration of a place and its culture through three powerfully articulated viewpoints, encompassing far more by their artistry than would have seemed possible, clearly, in 1899.