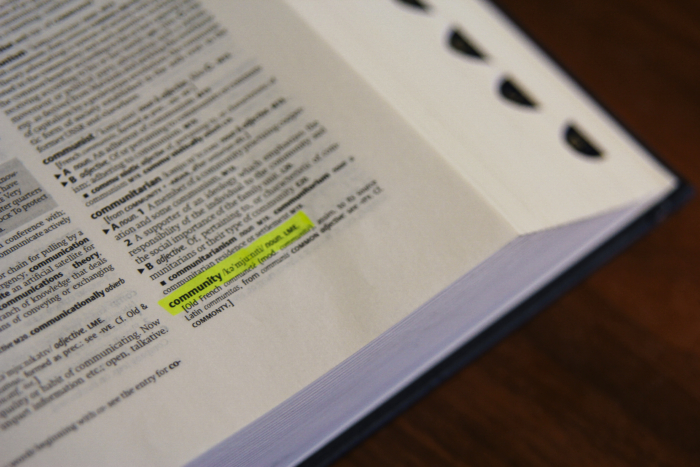

The Core Curriculum in Interdisciplinary Humanities, one of the hallmarks of the Scripps education, is a set of three courses that looks at the relationships between the historical production of knowledge and contemporary issues and debates. This year, Core I, the first of these courses and a common curricular experience for all Scripps students, has a new theme: “community.” Sixteen faculty members representing departments across the College worked together for many months to choose the new theme and craft a syllabus around it.

“Since Core I is a class every student takes, it’s one way we set an intellectual tone for our Scripps community and bring big issues to the table,” said YouYoung Kang, Elizabeth Hubert Malott Endowed Chair for the Core Curriculum in Interdisciplinary Humanities and associate professor of music.

“We look at what’s going on in the world, and we consider what students are thinking about.”

Each Core I theme has a term of three years; since 2013, the theme has been “violence.” As committee members discussed and researched areas of inquiry, sharing inspiration from their fields, Kang said a few themes began to emerge, including futures, the environment, bodies, and empathy.

“We eventually landed on a consensus: How do we define a community? What’s the need for it, and how do communities function?”

A course began to take shape, with source material as wide-ranging as the role of Demeter’s rituals in Greek communities, to literary explorations of identity by Virginia Woolf and Zora Neale Thurston, to contemporary takes on belonging and boundaries—from the famed annual desert celebration Burning Man to Rebecca Solnit’s recent essay, “Men Explain Things to Me.”

“The theme itself is just a word. The interesting part is the readings and lectures and subjects we’ll talk about,” said Babak Sanii, Core I faculty member and assistant professor of chemistry at the W.M. Keck Science Department.

“It was fascinating to me how every field had something to say about community in ways I hadn’t expected.”

How does chemistry relate to community? Sanii will draw on his scientific study of the self-assembly of molecules, featuring a lecture and readings that include a first-person narrative of a carbon atom and a white paper describing emergent behavior.

“My lab deals with how things form and un-form. Millions of molecules, with their own rules, come together and form structures, such as a cell membrane—a beautiful sphere,” said Sanii.

“How does that happen? It’s just simple design rules that create complex structures, with a freedom to form and break connections. And we can use this language to describe human systems, too.”

Sanii’s lecture falls within the first section of Core I, “Formation, Negotiation, and Transformation.” Beginning with Imagined Communities, a now-classic 1983 academic text by Benedict Anderson, the course moves through science, communal singing and dance, questions of citizenship, and the effect of gender and sexual orientation in forming personal and community identities. Core I then transitions into “Exclusion and Resistance,” connecting dots among a diverse set of topics such as the struggles of oppressed indigenous peoples, religious martyrdom, the prison-industrial complex, community among those living with disabilities, and the issues behind musical censorship. The final section of Core I, “Imagining Communal Possibilities,” looks forward while drawing from mythology, literature, and visual art. This coming fall, the course will also feature additional guest lectures on race and belonging in the U.S., the status of Syrian refugees, and perceptions of Islam in America.

“We live in a very multicultural society, a world where cultural differences are very visible and exposed,” said Claudia Arteaga, assistant professor of Spanish.

“But that doesn’t mean the rights of diverse communities are always recognized. Academia should be in constant dialogue with the world in which we live so we can challenge stereotypes and discrimination.”

Arteaga’s Core I lecture focus will be the testimonio of Rigoberta Menchú, a native and activist of the K’iche indigenous peoples of Guatemala, Mayan Indians who were targeted and killed by Guatemalan armed forces during the country’s decades-long civil war. Menchú’s social justice work in support of the rights of indigenous peoples won her the Nobel Peace Prize in 1992.

“Menchú was part of a culture that was resistant to national and international forces who were trying to impose policies on Guatemala that diminished the life of indigenous people,” said Arteaga.

“Her story is a profound lesson, a testimonial of a people in a struggle to survive, to literally keep their culture alive. That connection between culture and politics, culture and identity, is what made me want to teach this. I think her message, that people have a right to define in their own terms how they want to live, is very relevant today.”

Following the Core I courses, a selection of interdisciplinary Core II classes, many of which are team-taught, will delve into special topics to be defined this fall, and students will complete the curriculum with Core III, undertaking interdisciplinary research and creative projects rooted in “histories of the present.”

“It can be challenging for young students, still often so idealistic, to see that the world, and their community, is not perfect,” said Kang.

“We want them to explore how communities set boundaries and critique them at the same time. I’m excited for students to gain a rich and diverse concept of community and develop a new way to understand the world—where we are now, and where we might go from here.”